In some respects, cultural resource archaeology differs from traditional or academic research archaeology. Since the goal for cultural resource archaeologists is preservation, the emphasis is on the identification and assessment of archaeological resources rather than thorough excavation and interpretation of sites. In this sense, cultural resource archaeologists often “stop” just where traditional archaeologists “begin” – with the discovery of an archaeological site.

Archaeology is a destructive process, since the excavations that create a record of a site do so through effectively dismantling it. The intent of cultural resource management is preservation and conservation of archaeological resources. We excavate only as much as is necessary to determine the presence, nature, dimensions, integrity, and age of a site. Full excavations are conducted only when a site cannot be avoided and left in place. Even then, the emphasis is primarily on thorough recording of the site for more extensive analysis by researchers in the future.

Another difference is that while many archaeologists typically specialize in a specific geographic region or historical period, cultural resource archaeologists need to be generalists. A broad knowledge of the whole history of human activity in an area is needed for this type of archaeology. Whether a project area contains traces of a Native American camp from several thousands of years ago, a colonial-era settler’s cabin, or a late-19th century industrial mill – cultural resource archaeologists in the field need enough expertise to identify the artifacts and features of any type of site from any period of history.

Background Research & Screening

Most of the time, archaeological fieldwork actually begins in the library. The preliminary research for a project helps to see what might be found in a project area and to suggest what methods are likely to be most effective for the fieldwork. The background research involves a study of the local history, review of historical maps of the area, a search for known archaeological or historic properties in the vicinity, and a review of the environmental setting (including soil types, hydrography, and geology) of the project area. Working from this kind of information, a research and testing strategy is designed to reasonably ensure that any archaeological resources in the study area are found and identified.

Even with the most thorough background research, one can never know for sure whether there are or aren’t archeological resources present in an area. Sites are quite often found in unexpected places, so the only way to really find out is to go out into the field and start digging.

Phase I — Reconnaissance Survey

Sometimes referred to as a “Phase One Survey” or simply “Survey”, a Reconnaissance Survey is intended to do just that – to explore an area that may be affected by a state project, and to see what (if anything) is in the area that has the potential to be of historical or archaeological importance. The most common way of doing so is to dig a grid of shovel test pits (STPs) across the area.

STPs are small round units (40 centimeters diameter, less than a foot and a half) that are excavated by hand, and dug down through the various layers of soil until a “sterile” layer is reached – often to depths of between 2 and 4 feet on most occasions. A “sterile” soil layer is, in this sense, one that contains no artifacts or evidence of human activity and is a naturally occurring part of soil formation (i.e. a sub-soil “B-Horizon” that generally predates human occupation in an area).

The STPs are typically spaced 50 feet apart, which works out to an area sample of 16 STPs per acre. This sampling interval is close enough to be most likely to catch at least a glimpse of any buried archaeological resources, while still being as efficient as possible with the amount of work needed to test an area. The testing interval is shortened to 25 feet or less when artifacts are found or in a location where a site is strongly suspected (for example: near a map-documented structure or in an area where known sites are nearby).

Notes are recorded for each STP that document the depths and descriptions of the soils encountered, what (if any) artifacts are found, and general observations about the pit and its surroundings (e.g. “on a lawn” or “lots of crushed gravels present in the first layer”). Any artifacts found are collected and bagged, then labeled with the STP number and in what soil layer they were found (i.e. the “provenience” of the artifact). These field notes and collections provide the lead archaeologist with all the pertinent information to determine whether the cultural material and features found (if any) warrant a designation as an archaeological site.

If a site is found, then the question becomes whether the site is intact and/or significant enough to be eligible for the State or National Registers of Historic Places.

Phase II – Site Examination and Evaluation

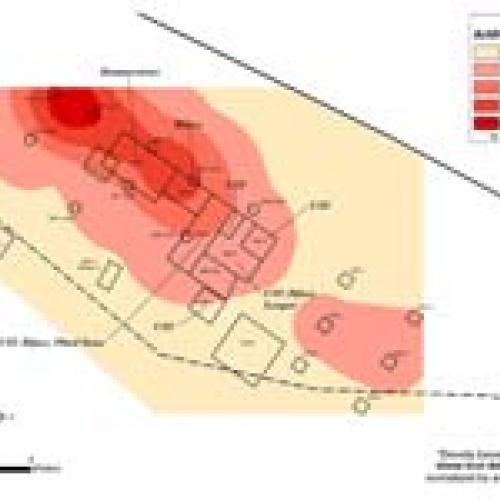

A Site Examination or “Phase Two” Survey is meant to gather enough archaeological data to decide if a site is “significant” and to clarify the horizontal and vertical limits of the site’s area. The significance of an archaeological site is basically determined by whether the site has archaeological integrity (i.e. it remains largely intact) and whether it can provide historical information about the place, region, or people associated with the site. The spatial limits of the site are important for planning the other projects in the area in order to avoid affecting the site any more than necessary.

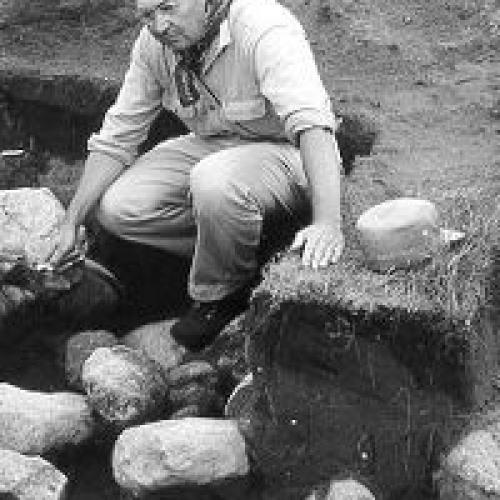

A site examination typically involves excavating more STPs at a smaller interval than during the survey, and excavating a small number of larger excavation units and/or trenches to expose parts of the site for closer study of its soil layers and features (e.g. a foundation or hearth). Again, all of these excavations are carefully recorded and mapped and all the artifacts collected and catalogued by provenience.

The intent of these test excavations is assessment, rather than interpretation, of an archaeological site. In a site examination, only a small percentage of the site’s area is tested intensively. Since the preferred outcome of cultural resource archaeology is to leave the site in place, a limited sample allows the archaeologists to make a determination about the integrity and significance of a site without removing more of the site’s resources than is minimally necessary.

In some situations, however, there is no way to avoid the site and leave it undisturbed. If the site has been determined to be eligible for the State or National Register of Historic Places and it cannot be avoided, then the site needs to be excavated and recorded in full.

Phase III – Data Recovery and Site Mitigation

Data recovery is a long and slow process, requiring extensive field excavations and exhaustive historical research. More often, some form of site mitigation is proposed that minimizes (i.e. mitigates) the effects of construction on the site as a whole. This could mean excavating part of the site while changing the construction plans to avoid the rest, or possibly coming up with some way to protect the site from the construction by designing around it or “capping” it with some protective barrier. These decisions are made through a process of consultation between the government agencies involved, professional archaeologists, and the public and other people that may have some special interest in the site (e.g. the local community, related families, and Native descendents or representatives).

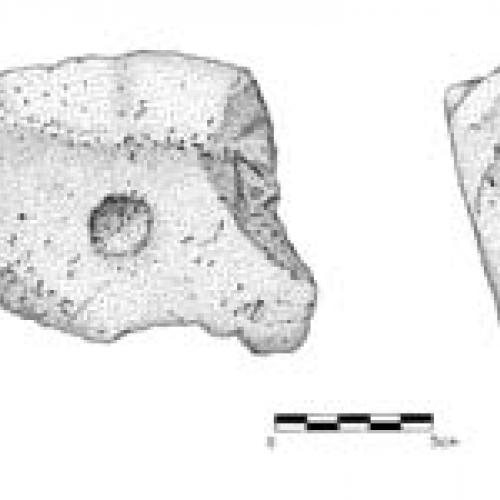

A Data Recovery (or “Phase III”) is what most people think of as “real” archaeology – large area blocks of units, grids and survey lines stretched across a site, and lots of dirt being meticulously and methodically excavated and recorded. The intent of a data recovery excavation is the full recording of any and all archaeological data from a site that would otherwise be lost. If a site goes to this phase of excavation, it means that the site is both historically significant and unavoidably threatened by construction. In these situations, the only recourse is to create as thorough a record of the site as possible.

While surveys and site examinations are intend to find and evaluate a site, a data recovery is meant to create as full an archaeological record of a site as can be done. This is accomplished through large-scale excavations of areas of interest identified in the prior phases combined with broad historical research on the location and its inhabitants. For historical sites, this can mean researching all available deed and census data related to the sites historical owners, old documents and letters, maps, newspaper articles, and any other references that can be found. For Native sites, it includes historical and archaeological reports about the site’s and regions prehistoric inhabitants and their way of life, consultation with tribal descendents, and comparisons with similar sites found throughout the state.

The intent of all of this work is to provide future researchers with any and all information they might need to analyze and interpret the site, since the site itself will no longer be available.