Shaker Seed Co. Labels, Collection New York State Museum

From the Collections: Shakers and the New York State Museum

2024 marks the 250th anniversary of the Shakers coming to colonial America. The Shakers were a small sect of Quakers that started in Manchester, England in 1747. They were formally known as the United Society of Believers in Christ’s First and Second Appearing. Because of the zealous fervor associated with their ritual dance, they were known as the “Shaking Quakers” or “Shakers.”

After migrating to New York in 1774, the Shakers became a communal Christian religious society that flourished in the late 18th and 19th centuries. Principles of their faith included celibacy, equality of the sexes, oral confessions of sins, pacifism, and withdrawal into their communities from the outside world.

The first American Shaker settlement was in Niskayuna (later called Watervliet), Albany County, NY. The second settlement was established in New Lebanon, Columbia County, where the first meeting house was constructed in 1784. Other Shaker communities were founded in Massachusetts, Connecticut, New Hampshire, Maine, Ohio, Kentucky, and Indiana. At the movement’s height, its total population reached about 6,000 in 19 separate communities.

To mark this anniversary, the New York State Museum will post an artifact from its Shaker Collection each month.

DECEMBER

As we close out the 250th anniversary of the Shakers coming to America in 1774, it is important to note the efforts of the Shakers themselves to preserve their own heritage at the New York State Museum.

When the Groveland community (Livingston County) closed in 1892, Eldress Ella Winship and Sister Jennie Wells moved to the Watervliet community, bringing the community’s possessions with them. Eldress Anna Case documented Watervliet’s history and artifacts, and in 1927, these women began collaborating with the New York State Museum (NYSM) to preserve their community's unique heritage. By 1938, only three Shaker women remained at Watervliet, leading to its closure and their relocation to Mt. Lebanon, which itself closed in 1947. Thanks to these women, many Shaker artifacts in the NYSM’s History Collection have a well-documented provenance.

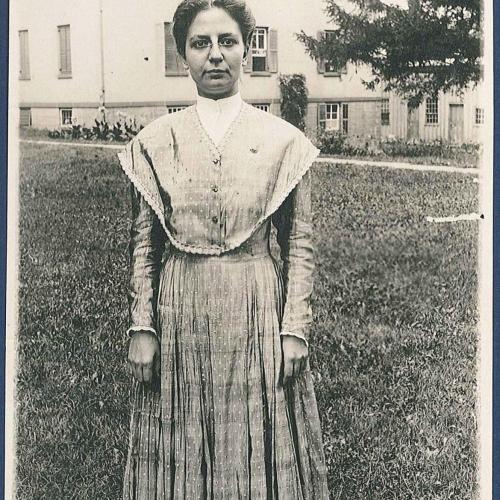

Jennie Wells and Ella Winship, c.1917

When the Groveland community (Livingston County) closed in 1892, Eldress Ella Winship and Sister Jennie Wells both moved to the Watervliet community. Both women documented most of the material from the Groveland community that was transferred to Watervliet, and eventually to the Museum.

New York State Museum Collection

Stone Bridge, South Family at Watervliet Community, c.1910

Each Shaker community was organized into various families with their own buildings. The leading family in each community was located closest to the meetinghouse and was always known as the “Church Family.” Subsequent families took the name of their geographic location within the community, for example the “North Family” or the “South Family.”

New York State Museum Collection

NOVEMBER

Shaker Meeting Houses are simple, functional structures that reflect the Shakers' values of humility, equality, and communal living. Designed with open interiors to accommodate their distinctive worship practices, these buildings are characterized by their plain, rectangular shapes and lack of ornamentation. They stand as significant examples of early American religious architecture and a testament to the ingenuity and craftsmanship of the Shaker communities.

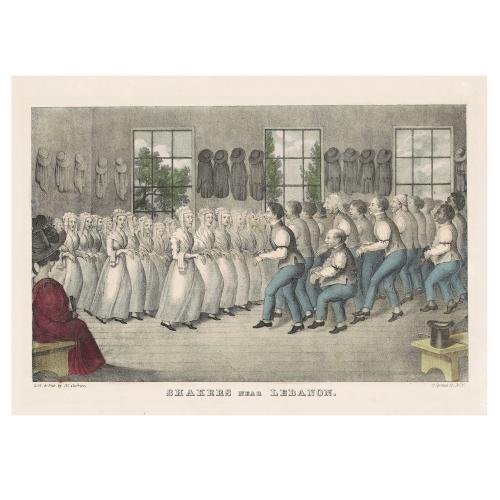

New York State -The Shakers of New Lebanon-Religious exercises in the Meeting house, 1873

This scene takes place inside the unique building that is the Mount Lebanon Meeting house. It depicts a circular dance where brethren and sisters are in separate circles, but are dancing together: clapping, singing and stomping during their worship service. "Observers from the World" line the built-in benches along the walls. Shakers welcomed guests to their meetings, hoping that they would gain converts.

(Image courtesy of the Library of Congress)

mary-dahm.jpg

Picture postcard of Mary Dahm

Shaker Museum Print, Photographic

https://shakermuseum.us/object/?id=17577

OCTOBER

The production and sale of “fancy goods” by Shaker women was an important source of income for Shaker communities in the early 20th century. Doll clothing and dolls dressed in Shaker-made clothing were popular items in shops in several Shaker communities. The doll clothing made by Shaker women mimicked their own outfits, including a cloak, bonnet, dress, and even underwear! These two examples, which came into the NYSM’s collections almost fifty years apart, were both made by Sister Mary Frances Dahm.

The first doll wearing a red cloak and purple dress, was recently acquired by the NYSM in 2024. It was made by Dahm for Shelia Bergin Plowinske, a young woman who lived with her family on the Shaker’s South Family Farm at Watervliet and who remained friendly with the remaining sisters after the Watervliet community shut down and they moved to Mount Lebanon. The second doll, pictured below seated in front of its packaging, was acquired in 1975 directly from Mary and her sister, Grace.

Mary Dahm, and her biological siblings Grace and Raymond, were brought to the Watervliet Shaker community after the death of their mother. When Watervliet closed, Mary and Grace moved to Mount Lebanon and then to Hancock, Massachusetts, as each community shut down. Recognizing the needs of the aging Shaker population around her, Mary sought out nurse’s training and served the community in that role for the rest of her life.

SEPTEMBER

Cloaks and Pen Wipes

As Shaker communities dwindled at the end of the 19th century, and agriculture and furniture-making were in decline, Shaker communities needed to find new sources of income. As a result, many communities in the Northeast opened stores that sold household “fancy goods” made by the Shaker sisters.

The design and making of hooded cloaks was one such successful enterprise for the Shakers. Using imported wool, cloaks of the same design worn by Shaker women, patented by Elders Emma J. Neale, were sold to women in the outside world.

In the interest of not being wasteful, the Shakers used wool scraps from cloak-making to make pen wipes, an important desktop accessory for dip and fountain pen use. The Shakers added scraps to small ceramic dolls, as seen in the photograph from Mt. Lebanon by William Winter. Shaker store records also list “kittie” and “water lily” designs.

AUGUST

In the Kitchen with the Shakers

In the early years of the Shaker Society, followers ate a meager diet as they struggled to attain sound economic footing. However, by the 1830s, as the communities grew in numbers and resources, the Shakers generally ate very well. Journals of the period record a rich diet of meats and fish prepared various ways, seasonal fruits and vegetables served fresh and preserved, and treats like doughnuts, cakes, and pies. Although the Shakers officially banned alcoholic beverages, including hard cider, beer and wine, documents indicate that the Shakers still purchased and consumed these products in quantity.

JULY

Double Cheese Press, c.1860

This device has a dual or double press for squeezing water from curds to make cheese. It was manufactured at the Hancock Shaker Village where dairy production was a major industry.

Cheese Basket, c. 1860

Baskets like this, made of woven splint, were used to strain water from whey curds that became cheese.

JUNE

Did you know that the Shakers were instrumental in bringing home gardens to life in the United States? Before they established themselves as high-quality furniture makers, their first major business involved garden seeds! The Shaker garden seed industry began in the late 18th century. Most farms at this time produced vegetables on a large scale and farmers would purchase seeds in bulk. The Shakers were the first to put their seeds into small packages, called papers, so that the average person could plant a small kitchen garden. Shakers placed the seed packets into wooden boxes with colorful advertising on the lid, brought the boxes to small country stores in the spring and collected money from the proprietor in the fall.

Shaker Seeds and Canned Goods

MAY

Shaker women were active in many aspects of community life that were not open to women in other communities—they were able to preach, were valued in community decision-making, and participated in a variety of work and industries. Shaker women were also vital in preserving their communities’ history, donating many items to the museum’s collections.

A new addition to the exhibition “From the Collections: Women Who Lead,” this mold was used for shaping bonnets worn by Shaker women. It was donated to the NYSM by Eldress Emma Neale, of Mount Lebanon. Shaker women's active role in the production of products for use by the Shakers and for sale to the secular world made them adept at choosing important tools, raw materials, and finished goods to donate to the museum, allowing us to tell the story of these industries.

APRIL

The Era of Manifestations

In the mid-19th century, the Shakers experienced a religious revival called the Era of Manifestations, or "Mother’s Work." With the gradual decline of Believers who had known Mother Ann Lee personally, new Believers sought to reconnect with the original messages of Shakerism.

From 1837 to the mid-1850s, this period saw a great deal of excitement and religious fervor in the communities. Meetings were closed to the “World’s People” as Shakers had visions, spoke in tongues, and communicated with spirits. Believers in each community were divinely inspired to consecrate the highest piece of land as a “feast ground” and install a “fountain stone.” The feast was a spiritual one, and the “fountain” offered the water of life for the Believers.

This fountain stone is the only surviving example of a fountain stone from a Shaker feast ground. It was installed in 1847 at the community at Groveland in Western New York. The carved inscription states in part, “Here have I opened a living fountain of holy and eternal waters.”

MARCH

Shaker Women's Legacy: Preserving History in New York State

The NYSM’s extensive collection of artifacts documenting Shaker communities in New York State would not exist without the foresight of Shaker women. Facing a shrinking population and closure of some Shaker communities in the early 20th century, Shaker women reached out and worked closely with the director and curatorial staff of the NYSM from 1927 through the 1940s. These women included Eldress Ella Winship, Eldress Rosetta Stephens, Sister Lillian Barlow, Eldress Emma Neal, and Sister Sadie Neale of Mt. Lebanon, NY, Eldress Anna Case and Sister Jennie Wells of Watervliet, NY, Sister Alice Smith of Hancock, MA, and Sister Aida Elam of Canterbury, NH. They were forced to make careful decisions, balancing the importance of preserving Shaker history through donations, while also keeping in mind the financial health of the remaining communities by offering some artifacts for sale. Thanks to their work, we can continue to study the influence and contributions of the Shakers throughout New York and beyond!

FEBRUARY

How the Shakers Championed Equality in Early America

The Shakers were revolutionary in their attitudes toward equality. To the Shakers, all are equal in the eyes of God, and therefore all are to be treated with respect. The Shakers accepted converts of any race or ethnicity to their communities as equal members. African Americans joined and held equal status with their white brethren inside the confines of the village.

Sister Phoebe Lane was born in Cornwall, NY, in 1785. Her father, Prime, joined the Shakers at Watervliet in 1802 accompanied by his daughters, Phoebe and Betty. When Prime rejected the Shakers, his daughters decided to remain. Because slavery was still legal in New York State, Prime sued the Society claiming his daughters as property. The New York State Supreme Court ultimately ruled that the women were free to act for themselves. Phoebe remained with the Watervliet Community for 74 years until she died in 1881.

JANUARY

For more information about the Shaker Collection at the New York State Museum, view the online exhibition, The Shakers: America's Quiet Revolutionaries:

https://exhibitions.nysm.nysed.gov/shakers/index.html